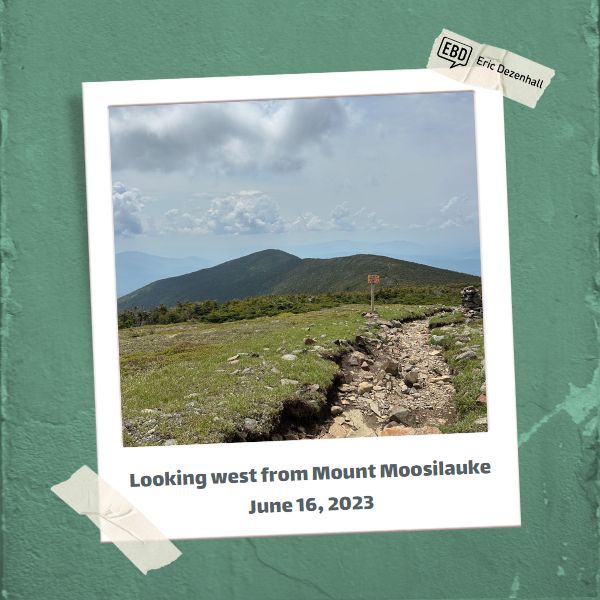

Forty-three years ago, I climbed Mount Moosilauke in New Hampshire as part of Dartmouth’s “freshman trip” program. From its near-5,000-foot peak, you can see a 360-degree panorama of the White Mountains of New Hampshire and Green Mountains of Vermont, the latter visible beyond the Connecticut River that skates from Quebec to Long Island Sound. On the map, these states look tiny, but from high on the planet, they are vast, commanding and very, very green.

I barely noticed this in 1980 because it was just another nature thing, like other nature things that were supposed to inspire wonder. Eh. I was more preoccupied with what you might expect from an 18-year-old: What was in store for me when I came down the mountain and started college in earnest, which was described unanimously by family, friends, and acquaintances as “the best years of your life,” as if by divine sanction.

I climbed Moosilauke again last week at the 40th (39th actually) reunion of the Class of 1984, a ritual I share with someone important to me. I paid serious attention to every step I took: Hiking up a mountain at 60 is a whole different game than it was at 18. I kept thinking about how every boulder had found its way from a cosmic roadside bomb thirteen billion years ago to this pathway up to a shelf of the solar system. From the peak, you can look around for hours and see everything in the world and nothing of the world at the same time.

At a memorial service for classmates we lost, there was a fleeting mention that college hadn’t been great for everyone, and this is the subject that brings me to ground. We look at the world differently as parents and grandparents (I am both) than we did at 18. At 18, it’s all about us, but now it’s all about them. Now that most of us are past the life stage when we are competing over who’s having more fun, we can listen to the stories about the challenges we’ve had with our children, some of us having to endure all-consuming worries that are bigger than anything geology can cough up.

Perhaps there are people who can “compartmentalize” their worries, but if there are, I’d like to invite them on a high-altitude hike, guide them to a cliff, and give them a little shove. Whoopsie. Parents obsess. Writers obsess. So, imagine being a parent and a writer. People like us really oughtn’t to be trusted to walk the streets let alone scale mountains.

In addition to the kid dramas that I hear from my contemporaries, I am a trustee at a small college not far from where I live, near Washington. Its former president and I used to discuss the difference between our generation and the millennial and Gen Zers who now swarm the republic. We were both gobsmacked by how many of them have serious problems with depression, anxiety, and basic executive functioning. I was no cool customer at 18, but I was aware that if a class began at 8:00, I would have to set my alarm clock, you know. . . before that time. Many young people struggle with this kind of thing on top of other mental health issues. My household has not been immune to such delights.

We can debate the causes of these phenomena, but the crisis manager in me is trained to distill things to simple, actionable counsel: I think there is a big problem with what we’ve been telling young people before they go to college because we put them under needlessly withering pressure. I’m not referring to the pressure to succeed; we know all about that. I’m thinking about the false expectation that college students are supposed to always be happy because these must be the Best Years of Their Lives, a swindle that implies they might as well disembowel themselves after graduation because it’s all downhill from here. Which, by the way, isn’t true.

In 1980, my crew had only the post-Woodstock rap of perpetual happiness to compete with. We had a “right” to it, according to a lame-brained interpretation of the Declaration of Independence, which was composed about a mile from where I was born. Anything less than euphoria was labeled “dysfunction.” There was the Animal House/Caddyshack culture of popular entertainment, the campus searches for the party that never was, the conceit that a distant echo of laughing voices represented a jubilee you had been excluded from, and the love interest that couldn’t differentiate you from plankton. I remember my parents asking me if I had anything going on in that department and I instinctively made up the name of a dude who got all the girls, thereby completely acing me out of the game. So omnipresent was my fictional nemesis Kurt Rossiter that decades later, I made him into a character in my latest novel False Light — and got back at him big time. In real life, I’m not vindictive; in fiction, I’m vicious.

It’s worse now for the young in the head sense. We’ve heard a lot about the perils of social media, but it’s become a glob of complaints that needs more focus: My issue with social media is the false promise of torrential glee that can never be scored.

Am I overreacting much? I don’t think so. I am familiar with multiple child suicides, substance abuse hardships, and psychiatric hospitalizations within my circle. Somewhere in between telling an adolescent that life’s a bitch and that it’s one big Willy Wonka golden ticket victory (featuring a chocolate river) is something more sober.

I’ve given a lot of advice during my career, that is, define reality: “Yes, I think your company can survive this, but you’ll spend a lot of money and absorb a hit to your reputation that will take a while to put behind you.” Interestingly, the fantasy template is overtaking my business as well. A big company with a serious problem came to me not long ago and didn’t react very well to my temperate advice.

“Let me guess,” I said. “You just met with [name of big consulting firm] and they showed you a PowerPoint that contained the phrase ‘A crisis is an opportunity.’”

The executives’ jaws dropped. They asked how I had known because this was exactly what had happened. My response was, “A crisis is not an opportunity. A crisis is a crisis. If you want to keep taking bong hits, hire them.”

I recently spoke to a Dartmouth-bound child of a relative (call him Michael) who asked if I had any wisdom to share. I was mindful that a family friend had recently lost a child grappling with growing-up issues to suicide. Michael seemed to be a sensitive type, so I said, “Don’t be too hard on yourself and don’t be too hard on the school. You don’t have to love everything or everybody right away. I didn’t. If you find meeting people and nailing schoolwork hard, it means you’re living in the world, not dwelling in a freakish exception to it where you’re some kind of mutant. If you’re nervous, fine. It’s also not the college’s job to fill every void. If you encounter someone smarter, richer, more gifted athletically, or better looking, well, you’re supposed to.”

“Did that happen to you?” Michael asked.

“Well, not better looking,” I deadpanned until he got the joke and laughed.

Michael told me he wasn’t the most fun kid in the world. I told him, “Either was I. I’m a lot more fun as a grandfather who takes a statin than I was in college. I was mature in college. I’m aggressively sophomoric now. If you’re not loving college, call me and I’ll tell you about everyone in my elementary school who vomited or wet their pants in class because I have a mental database of this stuff. You’ll be much happier if you don’t expect to be thrilled all the time. And if you have any self-discipline at all, stay off social media. Trust me; they’re all full of shit about their perfect lives. Nobody does everything. Nobody gets everything.”

I don’t know if advice like this would have helped everybody who didn’t love college during my era, but it would have helped me. It turns out that I loved plenty of college, but not all of it. In retrospect, the constant propagandizing by well-meaning people did the most harm. I didn’t have four-leaf clovers raining down on me. I know people who did. Life rarely evens out.

Things got better when I eventually figured out that shaking the cruel “best years of your life” commandment was the way forward. My most vivid memories are not of “fun,” but the depth of the experience. As my damage control career winds down (in favor of writing), I think the most rewarding cases I worked on were the ones where I set expectations better than competitors running a never-ending Ponzi scheme promising to “accomplish the impossible” — the actual phrase on one company’s website. Ah, yes, when there’s an oil spill, they’re going to convince the public that it wasn’t an oil spill at all, just a nice fossil fuel company shampooing the fish…

Four decades after ignoring the moss and granite panorama atop Mount Moosilauke, I was awestruck by how green everything still was. America had not, in fact, become a strip mall anchored by a CVS and a Chipotle. There was even fresh, bright green vegetation sprouting. I saw it all now. Perhaps it was because of age. Or because I was with someone my age with an eye for awe. Or maybe it was because I hadn’t been expecting it because no one was throttling me with commands about how perfect it was supposed to be.